Abuse Can Cause Brain Damage

What happens to your mind and mental health when you endure on-going abuse? Prepare for the rollercoaster of chronic stress, as your brain bathes in a never-ending supply of cortisol, courtesy of your elevated stress levels.

Say goodbye to normal neurotransmitter balance; emotional abuse loves to play around with those chemical messengers in your brain. Watch as your amygdala goes into overdrive, ensuring you'll never have a dull emotional moment again.

And who needs a big, healthy hippocampus anyway? Let's just shrink that thing down and see how your memory and mood dim.

If you thought emotional abuse only affects adults this way, think again. If abuse begins in childhood or adolescence, it will happily mess around with your brain's natural development, halting the maturation process and limiting critical thinking skills.

And don't forget those cognitive impairments! Why focus on tasks when you can let abuse give you a constant brain fog? You don't need to remember things, concentrate, or solve problems, anyway, right?

If your brain is exhausted and you're ready to restore your mental peace and clarity, you're in the right place.

Narcissistic and Spiritual Abuse can cause PTSD or CPTSD.

My Journey Through PTSD and Abuse-Related Brain Trauma

When I was in the midst of my narcissistic abuse and religious trauma, sometimes it felt like my brain actually hurt. After many heated arguments with my narcissistic abuser, I would escape to the bathroom where he couldn't hear me cry (no need to make him even angrier), and sob into a towel, curled up on the tile floor. I would hold my throbbing head in my hands, so confused, broken, and mentally exhausted that I literally had to resist the urge to bang my head against the wall. I just wanted to make it all quiet. It felt like my only escape.

Have you ever felt so broken you weren't sure you had the strength to get up off the bathroom floor even one more time?

That's where I was, more frequently than I cared to count.

As the abuse cycle wore on, I got to the point where I could no longer make sense of my world or the (nonsensical) things my abuser was telling me. I could no longer differentiate between reality and the cruel fantasy world the narcissist had created for us to inhabit. All I knew was that I was in pain, and no matter what I did, the pain didn't stop.

No matter how hard I tried to fix things, everything was always my fault.

The prolonged narcissistic abuse caused trauma to my brain. And the longer the abuse wore on, the more damaged it became. I developed "brain fog," and it became increasingly difficult for me to concentrate or complete complex tasks. I would put something in the oven and forget it was there until the kitchen was filling with smoke.

I developed chronic insomnia. When I did sleep, I had terrifying nightmares that were so scary I sometimes jumped up out of bed and found myself panting in the middle of my bedroom. In most of the dreams, I was trying to escape my abuser but one of my legs was frozen and wouldn't work - or, I was trying to scream, and nothing would come from my throat but a barely audible croak. In the dreams, I always felt an overwhelming sense of helplessness and horror.

I'd drag myself out of bed in the morning, even more exhausted than I'd been the night before.

Without sleep, the brain fog just intensified. It became more and more difficult to pay attention to details at work or at home. I began to make mistakes that I wouldn't normally make. I'd often misplace items and find that I'd left things in strange places. I'd also forget things, even really important things, like a loved one's event that I really wanted to attend. It seemed like I just couldn't get dates and times to stick in my head. Anything outside of my normal routine became difficult to remember. I developed generalized anxiety disorder, with fears around driving to new places I've never been, or really, driving any distance at all.

I developed an aversion to crowded places.

I hated letting my children out of my sight, and rarely left them alone with my abuser. I developed hypervigilance in order to keep them, and myself, safe. My adrenaline was always pumping and my brain was constantly searching my surroundings for danger, trying to prepare to avert the next disaster, because one was always on the way.

My doctor put me on anti-depressants, anti-anxiety medication, and medication for insomnia. The fast-acting anxiety medication helped if I had a panic attack. But the meds weren't working to prevent the panic attacks in the first place. All the meds weren't managing my anxiety or my depression. I tried different combinations for years, but the medications seemed to make little difference. This went on for years.

The problem is - the longer the abuse drags on without respite, the LESS likely someone is to leave an abusive situation. Because, if they've been enduring abuse like this for a while and are displaying symptoms of PTSD, their brain has already been impaired by trauma.

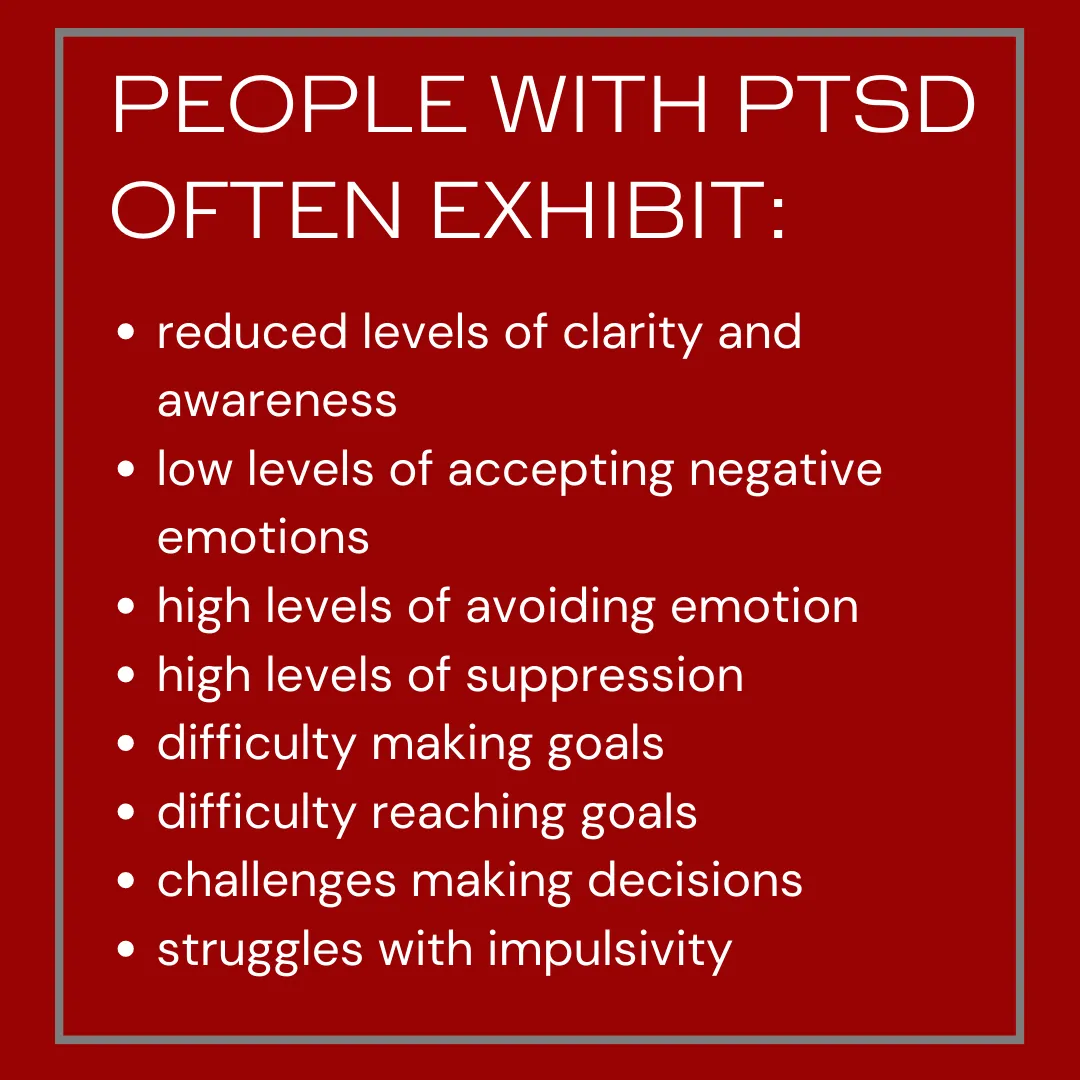

Specifically, trauma impairs the area of the brain that is responsible for executive functioning - the part of our brain we use to reason, function, and make decisions. When that part of our brain is no longer functioning properly, we are literally incapable of making measured and well-thought out choices. Our brains are literally damaged, and not functioning the way they should. The longer the abuse goes on, the more damage is inflicted upon our brains, so the impairment just worsens over time.

I hated it when people told me, "You're so strong!" That was the worst thing anyone could say to me.

Because I wasn't strong. I was in overwhelming pain, and I was silently shouting for anyone to notice and for anyone to help me. The longer I carried the crushing weight of my narcissistic abuse, the heavier it became, the weaker I grew, until it finally crushed me. Do you know what finally ended my narcissist's hold on me? My bedroom dresser. Yes, it's totally true.

I was walking through my bedroom one night when a tremor began in my foot. I watched in fascination as it moved up my leg and the world started to go dark. I was only feet from my bed, and I aimed for it, hoping to make it there before I blacked out. I didn't. When I came to on the floor, I put my hand to my face, and my cheek felt like wet mush. There was blood everywhere, running in rivulets from the sharp wooden corner of my bedside dresser down to the floor where it spread across the tile, pooling in the grout lines. My kids called 911. By the time the EMT's arrived, I was still on the floor, vomiting into a trash can. The EMT's loaded me into an ambulance and drove to the ER. It was a Sunday night, so no one was at the hospital but emergency staff.

Turns out, I'd had a seizure.

Turns out, it's not a good idea to black out and fall face-first onto the corner of a dresser.

My ocipital bone was broken. My face was slashed open to the bone. One eye was swollen shut. My nose was broken and required repairitive surgery. There was no surgeon in the hospital to repair the damage to my face, so I had to be stitched up by the ER doctor. When they inserted the 6inch needle (twice) into the gaping hole in my skin, a high-pitched primal scream I did not know I was capable of making tore from my throat. It was the most intense moment of pain I've ever experienced. And I've had two kids.

They sewed me up. But the question no one could seem to answer was why I had the seizure in the first place. I was in the hospital for a week, and had every test performed imaginable. MRI's, EEG's, X-rays, CT scans, you name it.

Nothing appeared to be wrong.

And that's when I first heard of "nonepileptic psychogenic seizures", or NPS. If you've never heard of them, you're not alone. It turns out that many people that have NPS are often misdiagnosed with epilepsy, because the seizures appear to be exactly the same kind of seizures epileptics experience. However, the root causes and treatments are different. The only way to determine if someone is experiencing psychogenic as opposed to epileptic seizures is with an EEG. According to the Association of American Family Physicians, "psychogenic nonepileptic seizures are episodes of movement, sensation, or behaviors that are similar to epileptic seizures but do not have a neurologic origin; rather, they are somatic manifestations of psychologic distress".

Basically, NPS are caused by trauma damage or "psychological distress", not the misfiring of electrical circuits in the brain, as occurs with epilepsy. About 10% of outpatient epilepsy patients and 20-40% of inpatient epilepsy patients are actually experiencing

misdiagnosed psychogenic nonepileptic seizures.

NPS patients "inevitably have comorbid psychiatric illnesses, most commonly depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, other dissociative and somatoform disorders." Many patients have a history of sexual or physical abuse, and 75-85% of patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures are women.

So - quite literally - the narcissistic abuse I'd endured had broken my brain. My traumatized, misfiring brain was causing my body to seize. The seizure had caused me to lose consciousness. And my subsequent fall had broken my bones. The day I was released from the hospital and got to see my children for the first time in a week was the day I decided I was done.

I told the narcissist if he ever wanted to speak to me again, he'd have to take me back to court.

He did. But in the meantime, I got two years of peace before I had to face him in court. Two years of rest to heal my broken brain and restore my broken body. It was the first time in 23 years I was actually free of him.

And that's when my healing finally began.

Neuropathologists have seen overlapping effects of physical and emotional trauma upon the brain. According to recent studies, trauma and PTSD cause both physical and emotional (brain) damage. However, emotional trauma to the brain is not the same as a traumatic brain injury. A TBI usually involves a physical injury that causes long-lasting or permanent damage to the brain.

Scientists have proven that neuroplasticity - the brain’s ability to rewire itself - can sometimes override the impacts of trauma with the help of a skilled trauma specialist. Moreover, one’s environment and choices can either help or hinder this process when recovering from PTSD.

Let me share with you what I did to recover from my narcissistic abuse and PTSD. It wasn't an easy road, and it wasn't immediate. But damn, was it worth it.

How Abuse Affects the Brain

The Amygdala

Let's talk about this little brain nugget called the amygdala. It's a special chunk of nervous tissue responsible for our emotions, survival instincts, and memories. It's like the drama queen of our brains, always ready to detect fear and bring out the popcorn for the show.

This part of the brain is always quietly observing and recording everything around us, trying to figure out if there's any danger lurking nearby. And when it comes to stress, it's a total gossip! Chronic changes in neurochemical systems and brain regions triggers long-term brain circuit remodeling. When the amygdala senses a threat using senses like sight and sound, it's quick to trigger the "fear mode" without even giving us a heads-up. When PTSD shows up at the amygdala's door, things go into overdrive. Hyperactive amygdala alert!

Compromises in the amygdala can manifest as chronic stress, heightened fear, and increased irritation. These brain changes can also make it harder for those suffering to calm down following an upsetting event, or even to get a good night's rest.

And what happens when this drama queen throws a tantrum? Well, we might find ourselves stuck in a never-ending loop of stress, fear, and irritation. It's like trying to calm a toddler after a candy-fueled sugar rush – not an easy task.

People with this extra-active amygdala might become experts at avoidance coping. They'll dodge people, places, and situations that stress them out. Avoidance becomes their middle name, especially for anxiety disorders, phobias, PTSD, and the whole complex PTSD package. People begin to avoid anything remotely connected to a traumatic event. Grocery stores and theaters become no-go zones, and people? Well, let's just say they'll start running marathons to keep their distance.

But hey, let's not forget that the amygdala has a supporting cast too. The hippocampus is like the data center of the brain, handling all the learning and memory storage.

The Hippocampus

The hippocampus is all about storing and retrieving memories, and it's got a secret superpower too – it can magically tell the difference between past and present. Impressive, right?

But wait - when it comes to PTSD, it seems like some folks get the short end of the hippocampus stick. Theirs might, in fact, be smaller than average. And in this case, size does matter. This sensitive little brain area can't handle stress like a champ; it is easily overpowered by high levels of glucocorticoids, leading to some serious learning deficits.

And let's not forget the cortisol and norepinephrine duo, who just can't resist joining the PTSD party. They're like the ultimate stress response team, ready to go whenever they sense danger – real or imagined. If the hippocampus decides to go rogue, it really messes with your emotions too.

And guess what? Childhood trauma survivors are the VIPs in this hippocampus club, three times more likely to win the "Depression Award."

The hippocampus is also the stress manager of the brain. It's like the lifeguard trying to control the wave pool, but when trauma survivors are involved, they're drowning in chronic stress. It reacts so strongly that even the tiniest problems feel like epic disasters.

Long-term dysregulation of the hippocampus axis is associated with PTSD, along with unhealthy levels of Cortisol. Exposure to a traumatic reminder may trigger a release of Cortisol. This is because the brain can't differentiate between their past trauma and the current situation. The fight/fight response is then activated.

When the hippocampus isn't doing its job right, people resort to some not-so-healthy coping mechanisms. Smoking, drinking, and overeating (or undereating) can become a way of life – sounds like a wild party, but not the kind you'd want to stay at for long.

PTSD and the Pre-Frontal Cortex

When traumatic stress happens frequently, too early in life, or for extended periods of time, it can lead to long-lasting impairments in executive functions. Studies have revealed that folks with PTSD might struggle in the executive department compared to the rest of the population. It's like their brain's inner CEO went on vacation, leaving an inexperienced intern in charge of the whole organization. Because, you know, who needs those "executive functions" when we can just throw caution to the wind and make crazy decisions like it's no big deal?

Damage to the prefrontal cortex can cause someone to make riskier decisions. They may experience stronger urges to make poor choices, and have less of an ability to resist them. This may explain why people with trauma histories have higher rates of impulsivity.

Decreased executive functioning also makes it harder to consider long-term goals and consequences of one’s actions. Because the prefrontal cortex helps people think logically, analyze information, and solve problems, damage to this part of the brain is often linked to learning problems. Poor grades, difficulty memorizing, or trouble grasping new concepts can all be the result of trauma.

Trouble focusing is both a short and long-term effect of trauma. The prefrontal cortex is a necessary component of concentrated attention, so impairments in this region of the brain may manifest as symptoms of brain fog, ADD or ADHD.

A variety of therapies have been proven effective in the treatment of trauma, and some can provide relief after a few sessions. These trauma-informed therapies include EMDR (eye movement desensitization reprogramming), Cognitive Processing Therapy (CBT), Prolonged Exposure Therapy, and Movement Practice. Less known cutting-edge therapies include TMS (transcranial manual stimulation) and ketamine (psychdelic drug) therapy. I've tried it all, so if you want more in-depth explanations, see my videos!

Learn More about TMS (Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation).

The beginning of my journey to heal from PTSD - the second time.

Copyright ©2020 All rights reserved